Well, things here are winding down. There is so much I want to see in Berlin, but not enough time to do all that and finish up work. Things are finally coming together though, and

Joe and I are getting close to having some sort of presentation ready for the project we have been working on all term (and will continue to work on after this trip is over). We are in the process of setting up a website to house the project, and the other night we were writing some content for that page. The little background paragraph we were working on introduced some cool ideas, and the next thing we knew, we had a mini-essay on the history of mapping. It sets the stage for our project, introducing the concepts that really are the foundation of this sort of mapping exploration. So, for anybody who is interested, here it is, in its current form:

The Evolution of Maps as a Means of Representing Space

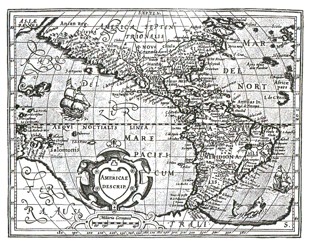

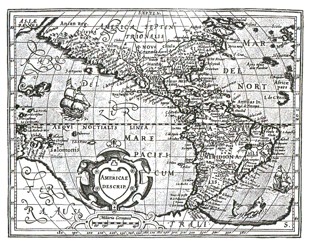

Maps, as a tool used in representing place, have been evolving throughout history according to a pattern reflecting both their purposes and the technologies that constrain them. The evolution of maps to this point can be characterized as a continuing process of more accurately representing physical places and their relationships in a way that precisely mirrors their visual appearance. With the digital age, technology has rapidly pushed visual precision to new levels, to the extent that it is appearing that accuracy, at least as perceived through the sense of sight, is beginning to approach its limits. As the traditional mapping sensibility is exhausted, the desire for accurate portrayal of place will naturally extend to the other senses, which can convey place in ways that the sense of sight has never been able to. Sound, emotions, feelings, and a myriad of other forms of perception will be incorporated into maps of the future through artistic means to better embody the places we encounter. As technology makes it increasingly feasible, the desire for “true” portrayals of space will lead people to art because art has, and always will be, the most appropriate means of expressing how something is in all its complexity.

The history of maps is a narrative that is intimately linked to mankind’s ability to gather and disseminate information. In the past, peo

ple relied on word-of-mouth stories of far-off places. As the knowledge base expanded and humans developed needs that required finding specific locations that involved complex directions, it became necessary to record one’s conception of space in a more permanent, visually-depictive manner. This is where mapping emerged as a key element of culture. Originally hand-drawn, and more recently, thanks to modern-day technology, cheaply mass-printed, maps made accessible a representation of the world in a portable form.

In this age of computers, information about place has made the jump to the Internet, and mapping has followed as well. Now, huge archives of maps may be accessed, searched, and manipulated from the convenience of a comfy armchair, at no cost to the user. Through online interfaces, such as Google Maps, Yahoo Maps, and Mapquest, a user need only type in departure and destination points, and a map appears with a colored line tracing the path between the locations. Places are connected in a web more tightly than ever, and mapping seems to have reached a new level of accessibility.

In the ever-expanding Internet full of cutthroat competitors, digital mapmakers needed to find a new direction in which to improve, and accuracy became a focus. In 2005, Google released a new mapping platform, Google Earth. This program goes beyond providing a digital version of paper maps by showing the globe as a fabric of full-color satellite images. Users can see the whole world, zooming in on areas of interest, rotating the terrain, and seeing in surprising detail the homes, cars, people, and trees on streets they have previously known only as names on a map.

Google went a step further in visually representing objects in space with the introduction of SketchUp – 3-D model-making software that allows users to build and import buildings into Google Earth – a step that puts mapmaking, or at least a facet of it, into the hands of the map user. With its photo-accurate, satellite capabilities and its robust communal network, Google Earth has become today’s most digitally advanced, public map. While there still is room for improvement in the area of magnification, the threshold of true, visual representations of physical space now appears to be within reach: a 3-D, perhaps live, Google Earth with a finer zoom.

Even if one were to follow the platform’s precision-progression along its seemingly asymptotic advance to infinity, Google Earth would still never be able to adequately represent real places because it can only do so through one sense: the sense of sight. There would still be room for mapping to grow, even in the face of visually-depictive perfection, because the world we live in is experienced through all the senses, not just sight.

Emotion. Sound. Feeling. All of these will be incorporated into maps of the future as people endeavor to better encapsulate the complexity of place. It seems only natural that art will be the form of expressing place in all its intricacies because the reality of a place is far too complex and subjective for anything but art to be able to adequately describe it. We are keenly aware of the fact that our experiences and perceptions are subjective, that they are unique and personally meaningful expressions of reality. Thus, if people desire to accurately represent their significant places in a map context for other people to experience and view in relationship to the surrounding geography, the Google Earth of tomorrow will be the avenue of creative self-expression by which they can best do so. This is the focus of our project: we are exploring the possibilities of the Google Earth medium as an artistic platform for representing place.